“And He placed firmly‑set mountains upon the Earth, lest it should shake with you.”

Qur’an 16:15

Table of Contents

1.0 Overview

The concept of mountain stabilisation can be explored through both modern geology and the Qur’anic description of mountains. Contemporary earth sciences describe mountains as deep‑rooted structures that contribute to the mechanical stability and long‑term equilibrium of the Earth’s crust [1][2]. Concepts such as isostasy, crustal roots, and tectonic stress distribution all highlight the stabilising role played by major mountain belts [3][4].

The Qur’an, revealed in the 7th century, presents mountains using language that associates them with firmness, anchoring, and stability. The material that follows examines the scientific understanding of mountains, the Qur’anic terminology and classical exegesis, and the extent to which there is a meaningful convergence between these perspectives.

1.1 Key Scientific Evidence

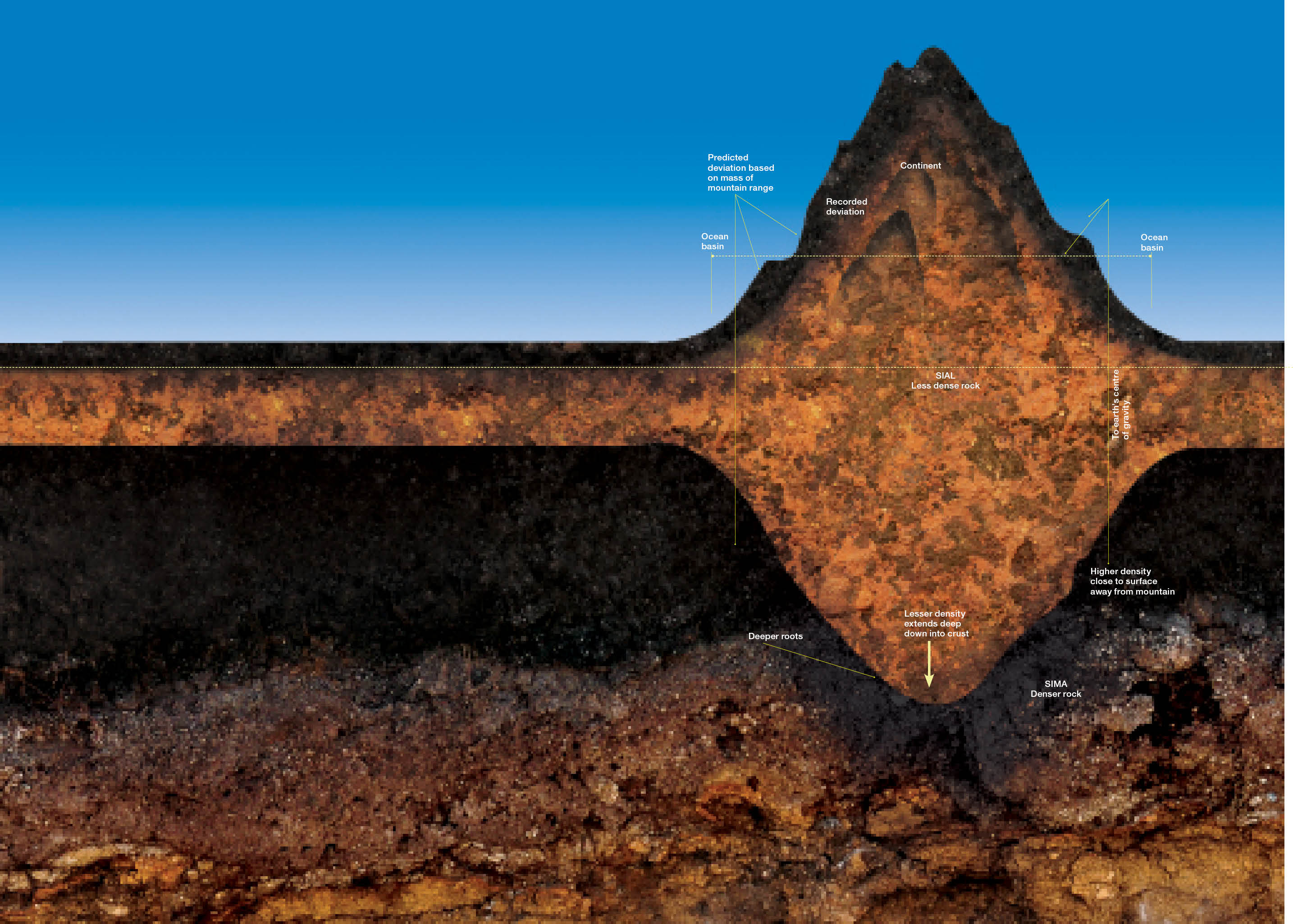

1.1.1 Mountain Roots and Crustal Anchoring

Modern geology recognises that many large mountain ranges possess deep crustal roots extending far beneath the surface [1][2]. These roots form when tectonic plates collide, forcing thickened crust downward into the mantle. This deep anchoring increases the rigidity of the surrounding crust and contributes to its long‑term mechanical stability. Mountains are therefore not merely surface features but integral components of the lithosphere’s structural framework.

1.1.2 Isostasy and Vertical Equilibrium

The principle of isostasy describes how the Earth’s lithosphere “floats” on the more ductile asthenosphere beneath it [3]. Mountain ranges, with their elevated mass and deep roots, participate in this balancing system. When erosion removes material from the surface, the crust rises; when mass accumulates, it subsides. This dynamic equilibrium helps maintain crustal thickness and prevents extreme vertical imbalances, contributing to the long‑term stability of continental regions.

1.1.3 Tectonic Stress Distribution

Mountain belts form along convergent plate boundaries, where tectonic plates collide and compress [4][5]. Their presence influences how stress is distributed within the lithosphere. The mass and rigidity of mountains help absorb, redirect, and localise tectonic forces, reducing the extent of deformation in distant continental interiors. While mountains arise from intense tectonic activity, their established structures contribute to a more organised distribution of stress across the crust.

1.1.4 Seismic Wave Modification

Although mountains do not prevent earthquakes, they influence how seismic waves travel through the crust [5][6]. Variations in crustal thickness, density, and structure beneath mountain ranges can refract, reflect, and attenuate seismic energy. This can reduce the spread of seismic motion into adjacent regions. Mountains therefore play a role in shaping the Earth’s seismic behaviour and contribute to the overall mechanical response of the crust.

1.1.5 Long‑Term Continental Stability

Over geological timescales, the formation, erosion, and isostatic adjustment of mountains contribute to the long‑term stability of continents [2][3][6]. Mountain building thickens the crust, while erosion and rebound gradually reshape it into more stable configurations. This cyclical process helps maintain continental landmasses and prevents large‑scale collapse or excessive thinning. Mountains are thus central to the Earth’s ability to sustain stable, habitable land over millions of years.

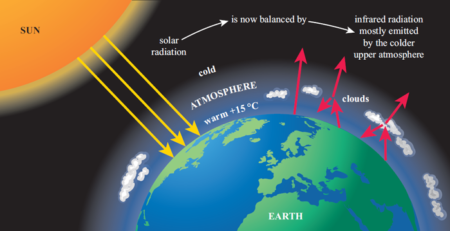

Figure 3.

2.0 The Qur'an

The Qur’an describes mountains using language that emphasises firmness, anchoring, and stabilisation.

وَأَلْقَىٰ فِي الْأَرْضِ رَوَاسِيَ أَن تَمِيدَ بِكُمْ

“And He placed firmly‑set mountains upon the Earth, lest it should shake with you.”

Qur’an 16:15وَجَعَلْنَا فِي الْأَرْضِ رَوَاسِيَ

“And We placed firm mountains upon the Earth.”

Qur’an 21:31

These verses associate mountains with stability and firmness, using terminology that conveys anchoring and preventing excessive shaking.

2.1 Lexicon

رَوَاسِي (rawāsi) — “firmly anchored, fixed, stabilising.” Derived from the root ر س و, which conveys the meaning of anchoring or holding something in place. Lisān al‑‘Arab describes rawāsi as objects that stabilise and prevent movement [7].

أَن تَمِيدَ (an tamīda) — “lest it sway, tilt, or shake.” Classical lexicons define māda as movement, oscillation, or instability [7].

Morphological Note

Rawāsi is a plural noun in the intensive form, indicating not merely mountains, but mountains emphasised in their role as stabilising structures.

2.2 Early Exegesis

Al‑Tabari (923 CE)

Interprets rawāsi as mountains placed to stabilise the Earth and prevent excessive shaking. لِئَلَّا تَمِيدَ بِأَهْلِهَا “So that it does not sway with its inhabitants.” [8]

Ibn Kathir (1373 CE)

Explains that mountains were created to anchor the Earth and maintain its stability. ثِقَالًا تُثَبِّتُ الْأَرْضَ “Massive structures that stabilise the Earth.” [9]

Al‑Qurtubi (1273 CE)

Emphasises that mountains act like pegs or stakes driven into the ground, preventing movement. جِبَالًا ثَوَابِتَ لَا تَضْطَرِبُ “Firm mountains that prevent instability.” [10]

3.0 Alignment

Scientific Claim

Mountains possess deep roots.

Mountains stabilise crustal thickness.

Mountains distribute tectonic stress.

Mountains influence seismic behaviour.

Mountains contribute to long‑term continental stability. [1][2][3][4]

The Qur’an’s Statement

Mountains are firmly set.

Mountains prevent excessive shaking.

Mountains are described as stabilising features. [7][8][9][10]

Conceptual Alignment

✔ Both describe mountains as stabilising structures.

✔ Both emphasise firmness and anchoring.

✔ Both associate mountains with preventing excessive movement.

✔ Both describe mountains as integral to the Earth’s stability.

Mountains as “Anchors”

The Qur’anic term rawāsi conveys the idea of anchoring and stabilisation. Modern geology describes mountains as deep‑rooted structures that anchor and stabilise the crust. This conceptual resonance is striking, especially given the absence of geological knowledge in the 7th century.

4.0 Scholarly Remarks

Below are a number of Scholars and Scientists that have made intriguingly positive references to Qur’an and this topic:

Alfred Kroner (German Geologist)

Described Qur’anic geological statements as “remarkably accurate” [11].

Yoshihide Kozai (Japanese Astronomer)

Said the Qur’an contains “true scientific facts” unknown in the 7th century [12].

George Smoot (Nobel Prize Astrophysicist)

Noted that the Qur’an’s descriptions align with modern scientific understanding [13].

E. Marshall Johnson (American Scientist)

Commented that the Qur’an describes natural phenomena with “remarkable accuracy” [14].

William Hay (American Scientist)

Acknowledged scientifically consistent descriptions in the Qur’an [15].

5.0 Improbability

What is the likelihood that this was authored by an unlettered man 1400 years ago in the middle of a desert?

5.1 Scientific Knowledge in 7th‑Century Arabia

No concept of tectonic plates. No knowledge of crustal roots. No understanding of isostasy. No geological instruments or models. No scientific tradition in the Hijaz related to geophysics.

5.2 Dominant Views of the Time

Ancient cosmologies viewed mountains symbolically. Greek and Roman models lacked tectonic theory. No civilisation proposed mountains as stabilising crustal structures. No ancient model described deep mountain roots.

5.3 Argument for Improbability

- The Qur’an describes mountains as stabilising structures firmly set into the Earth.

- Modern geology confirms that mountains possess deep roots and contribute to crustal stability.

- No scientific model in 7th‑century Arabia proposed deep crustal roots, isostasy, or tectonic stabilisation.

- No civilisation at the time described mountains as stabilising features of the lithosphere.

- The conceptual alignment between Qur’anic descriptions and modern geophysics is historically unexpected.

- The absence of geological knowledge, scientific institutions, or observational tools in the Hijaz makes a natural explanation unlikely.

- The convergence between Qur’anic language and contemporary geological understanding is therefore difficult to attribute to human knowledge of the era.

6.0 References

[1] Press, F. & Siever, R. (2001) Earth. New York: W.H. Freeman.

[2] Fowler, C.M.R. (2005) The Solid Earth: An Introduction to Global Geophysics. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3] Watts, A.B. (2001) Isostasy and Flexure of the Lithosphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4] Kearey, P., Klepeis, K.A. & Vine, F.J. (2009) Global Tectonics. 3rd edn. Oxford: Wiley‑Blackwell.

[5] Stein, S. & Wysession, M. (2003) An Introduction to Seismology, Earthquakes, and Earth Structure. Oxford: Blackwell.

[6] Turcotte, D.L. & Schubert, G. (2014) Geodynamics. 3rd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[7] Ibn Manzur (1883) Lisān al‑‘Arab. Beirut: Dār Ṣādir. (Original work published 1290–1311 CE)

[8] Al‑Tabari (2001) Jāmiʿ al‑Bayān ʿan Taʾwīl Āy al‑Qurʾān. Cairo: Dār Hajr. (Original work published 923 CE)

[9] Ibn Kathir (1999) Tafsīr al‑Qur’ān al‑ʿAẓīm. Riyadh: Dār Ṭayyiba. (Original work published 1373 CE)

[10] Al‑Qurtubi (1964) Al‑Jāmiʿ li‑Aḥkām al‑Qurʾān. Cairo: Dār al‑Kutub al‑Miṣriyya. (Original work published 1273 CE)

[11] Kroner, A. (1982) Interview with the Commission on Scientific Signs.

[12] Kozai, Y. (1982) Interview with the Commission on Scientific Signs.

[13] Smoot, G. (2009) Public lecture on cosmology and the Qur’an.

[14] Johnson, E.M. (1984) Interview at the First International Conference on Scientific Signs.

[15] Hay, W.W. (1984) Interview at the First International Conference on Scientific Signs.

[16] Lindberg, D.C. (1992) The Beginnings of Western Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[17] Ragep, F.J. (1996) ‘The Medieval Islamic Astronomical Tradition’, in Taton, R. & Wilson, C. (eds) The General History of Astronomy, Volume 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Note: The Qur’an is not a science textbook. The aim is to highlight noteworthy convergences that invite deeper reflection on the signs and truth of the divine.